By Cecelia Wood, Winter SCIART 2021

My name is Cecelia Wood, and I’m graduating this spring with a chemistry major and art history minor from St. Mary’s College of Maryland. If you know me now, it might be hard to believe that I never wanted to be a scientist. In high school, I told anyone that would listen that I wanted to do “anything but STEM”. A high school art history class had led me to art conservation. Nothing seemed more worthy to me than preserving human history and maintaining the beauty of art for generations to come. I had my sights set on being an art history major, but my concerned mother convinced me to add a chemistry major as a backup plan. No problem, I thought, this will just make me a better candidate for grad school.

I arrived at St. Mary’s excited to begin my art history classes and expecting to tolerate my chemistry classes, but something unexpected happened: I began to love chemistry. I felt as though the world was opening before my very eyes each class (ok, maybe not during the classes that we focused on naming compounds correctly). I realized that I enjoyed my chemistry classes for the same reason I enjoyed my art history classes: I left each class with a greater understanding of the world around me. I’ve had my ups and downs in both types of classes, but chemistry made me feel like I could do things that no one had ever done before. Eventually, I had to decide which major to drop down to a minor; though it felt a little bit like cutting off a limb, I decided just to minor in art history.

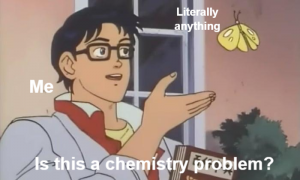

To me, everything is a chemistry question. I love taking complex processes and breaking them down to what is happening on the molecular scale. Perhaps this is why I really enjoyed the Winter SCIART program. The type of DFT computations we were working with generally have an upper limit of 150-ish atoms, so it’s necessary to reduce phenomena down to the bare essentials. Even though I was totally out of my element with the computational work, I was still breaking reactions down to the molecular scale (Layla did an excellent job summarizing all of the work we did, so I’ll direct you here instead of re-explaining everything). I was so happy to see that conservators and conservation scientists understand the value of looking at things from a chemical perspective. Sometimes, the answer to a question plaguing them was as simple as the periodic trends we learn in General Chemistry; of course, implementing a solution to a conservation problem is a much more difficult endeavor, but it’s amazing how much general chemistry is involved in art conservation.

It’s important for chemists to understand that the real-world implications of what they learn are only bound by their ability to find them. Whether you’re synthesizing organic dyes to image cancer cells, removing persistent organic pollutants from groundwater, or determining if the filigree on a piece of jewelry is authentic, a molecular level of understanding will always be beneficial. This discipline needs young chemists to come in and think up brilliant new solutions to the dangers that aging artworks face. I will always be grateful to the SCIART program for reminding me of that. The SCIART program is the only program I’ve done that truly understands the value of both the humanities and the sciences and recognizes how both have shaped the world. I hope that everyone gets to experience the beauty of interdisciplinary work like I did during the SCIART program.